An international conference was organized by the Arminius Vámbéry Centennial Committee, the Eötvös Loránd University and the Research Centre for the Humanities on September 13, 2013, on the 100th Anniversary of Arminius Vámbéry’s Death in Budapest, as a part of the Hungarian and international programs of the Vámbéry Memorial Year. Ármin Vámbéry (1832–1913), a Hungarian orientalist, Turkologist and traveller died a hundred years ago. A week earlier, the first of the series of scholarly events was organized in Ankara by the Turkish Linguistic Society, after this conference, the Istanbul University will have a commemoration, then a conference will be held in Iran and finally in Dunaszerdahely, where Vámbéry spent his childhood. (For the Hungarian series of events, see here.)

An international conference was organized by the Arminius Vámbéry Centennial Committee, the Eötvös Loránd University and the Research Centre for the Humanities on September 13, 2013, on the 100th Anniversary of Arminius Vámbéry’s Death in Budapest, as a part of the Hungarian and international programs of the Vámbéry Memorial Year. Ármin Vámbéry (1832–1913), a Hungarian orientalist, Turkologist and traveller died a hundred years ago. A week earlier, the first of the series of scholarly events was organized in Ankara by the Turkish Linguistic Society, after this conference, the Istanbul University will have a commemoration, then a conference will be held in Iran and finally in Dunaszerdahely, where Vámbéry spent his childhood. (For the Hungarian series of events, see here.)

The conference was opened with welcome addresses by Professor Miklós Maróth, Vice-President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and President of the Arminius Vámbéry Centennial Committee. Professor Barna Mezey, Rector of the Eötvös Loránd University, Zsolt Németh, Minister of State for Foreign Affairs of Hungary and Ilan Mor, Ambassador of Israel in Budapest also addressed the conference.

The conference was opened with welcome addresses by Professor Miklós Maróth, Vice-President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and President of the Arminius Vámbéry Centennial Committee. Professor Barna Mezey, Rector of the Eötvös Loránd University, Zsolt Németh, Minister of State for Foreign Affairs of Hungary and Ilan Mor, Ambassador of Israel in Budapest also addressed the conference.

The main topic of the morning session was “Vámbéry the scholar and political expert”. Academician György Hazai, his biographer praised his significance as a traveller, an ethnographer, a linguist, and as the founder of a new discipline, Turkology.

István Vásáry, Professor of the Turkish Philology Department of the Eötvös Loránd University, had a lecture titled “Arminius Vámbéry, a pioneer of Turkic studies” on the scholarly significance of Vámbéry.

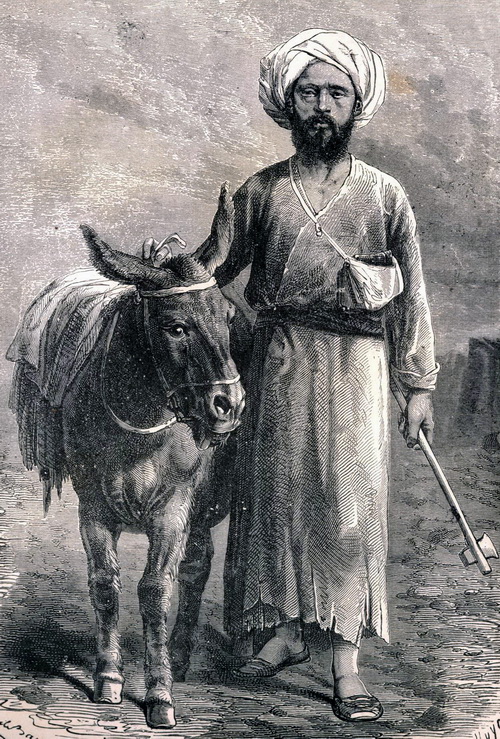

Arminius Vámbéry (1832–1913), outstanding figure of Hungarian scholarship and history of science can be considered  one of the founders and pioneers of a new branch of learning, that of Turkology. On account of his famous Central Asian travel in 1862–1864 Vámbéry can be regarded as an expert of the Islamic world, whose main field of expertise was Turkey, Iran and Central Asia. As scholar he was a founder of Turkology, and as traveller he was an explorer of Central Asia. In his understanding Turkology must expand its interest to all Turkic peoples and cultures, not only to the Ottoman-Turks but to the Asiatic Turkic peoples as well. In addition, a special task of Hungarian Turkological research is to pay attention to the different layers of Turco–Hungarian contacts (pre-ninth-century contacts prior to the conquest of the Carpathian Basin, Pecheneg–Cuman and Hungarian relationship in the 10th–13th century and the age of Ottoman domination in the 16th–17th century). One of the most important works of his Turkological research is The Turkic Race (1885), the first European monograph in which he made an attempt to get rid of the Ottoman-centred European view of Turkology and to include all Eurasian Turkic languages and peoples into the orbit of research. Another, equally significant field of his activity was laying foundation of East-Turkic (Chagatay) philology. His Ćagataische Sprachstudien (1867) was among the earliest East-Turkic chrestomathies published in Europe. Besides his Turkological activity Vámbéry was also intensely engaged in problems concerning the origins of the Hungarians and early Hungarian history. Although in this field he put forward some controversial theories, his thought-provoking ideas essentially contributed to a better understanding of early Hungarian history.

one of the founders and pioneers of a new branch of learning, that of Turkology. On account of his famous Central Asian travel in 1862–1864 Vámbéry can be regarded as an expert of the Islamic world, whose main field of expertise was Turkey, Iran and Central Asia. As scholar he was a founder of Turkology, and as traveller he was an explorer of Central Asia. In his understanding Turkology must expand its interest to all Turkic peoples and cultures, not only to the Ottoman-Turks but to the Asiatic Turkic peoples as well. In addition, a special task of Hungarian Turkological research is to pay attention to the different layers of Turco–Hungarian contacts (pre-ninth-century contacts prior to the conquest of the Carpathian Basin, Pecheneg–Cuman and Hungarian relationship in the 10th–13th century and the age of Ottoman domination in the 16th–17th century). One of the most important works of his Turkological research is The Turkic Race (1885), the first European monograph in which he made an attempt to get rid of the Ottoman-centred European view of Turkology and to include all Eurasian Turkic languages and peoples into the orbit of research. Another, equally significant field of his activity was laying foundation of East-Turkic (Chagatay) philology. His Ćagataische Sprachstudien (1867) was among the earliest East-Turkic chrestomathies published in Europe. Besides his Turkological activity Vámbéry was also intensely engaged in problems concerning the origins of the Hungarians and early Hungarian history. Although in this field he put forward some controversial theories, his thought-provoking ideas essentially contributed to a better understanding of early Hungarian history.

Prof. Dr. Mustafa Kaçalin Turkish linguist, the President of the Turkish Linguistic Society in Ankara, who was the organizer of the very successful Vámbéry conference in Ankara the previous week, had a lecture titled “Arminius  Vámbéry and his Eastern-Turkic research (Ćagataische Sprachstudien)”, which drew the attention to Vámbéry’s linguistic discoveries in connection with the languages of Central Asia.

Vámbéry and his Eastern-Turkic research (Ćagataische Sprachstudien)”, which drew the attention to Vámbéry’s linguistic discoveries in connection with the languages of Central Asia.

Vámbéry’s well-known study, the Ćagataische Sprachstudien was the first basic monograph in Europe containing the grammar, chrestomathy and dictionary of this language. In this book that was published exactly 145 years ago Vámbéry made the first attempt to define the Chagatay language and to describe its spread both chronologically and geographically. Vámbéry published the original texts in Arabic script without Latin transcription, accompanied by German translations. In light of the modern data one is often compelled to correct Vámbéry’s readings; however, the actuality of the work is demonstrated by the fact that it was reprinted in Amsterdam, in 1975 and it can also easily be found on the internet. The presentation treated a few selected parts of the work and gave an analysis of the dictionary.

Professor Jacob Landau from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem gave his lecture on Vámbéry, the political expert, with the title “Arminus Vámbéry and Abdul Hamid II”.

By his own account, Arminius Vámbéry had a special favoured relation with the Sultan Abdul Hamid II. Vámbéry’s  published works declare that he was a confidential adviser to the Sultan, who honoured him with invitations to his table and with lengthy private audiences. Vámbéry used his influence, for example, by arranging an audience, in 1901, with the Sultan for Theodor Herzl, the founder of the World Zionist Organization. Vámbéry, a conscientious scholar, soon enough noted the Sultan’s autocratic tendencies which he reported in his writings but still attempted to mitigate his criticism by praising the Sultan’s interest in public education and in commerce. Abdul Hamid, however, was hurt by Vámbéry’s criticism. Furthermore, the Sultan suspected Great Britain’s territorial designs and praised Russian policies. Vámbéry took a diametrically opposed view on foreign affairs which he carefully elaborated in his meetings with the Sultan. Thus their relations began to cool and found a final expression in a detailed critical paper published by Vámbéry in a London monthly in 1909 after the Sultan’s deposition by the Young Turks.

published works declare that he was a confidential adviser to the Sultan, who honoured him with invitations to his table and with lengthy private audiences. Vámbéry used his influence, for example, by arranging an audience, in 1901, with the Sultan for Theodor Herzl, the founder of the World Zionist Organization. Vámbéry, a conscientious scholar, soon enough noted the Sultan’s autocratic tendencies which he reported in his writings but still attempted to mitigate his criticism by praising the Sultan’s interest in public education and in commerce. Abdul Hamid, however, was hurt by Vámbéry’s criticism. Furthermore, the Sultan suspected Great Britain’s territorial designs and praised Russian policies. Vámbéry took a diametrically opposed view on foreign affairs which he carefully elaborated in his meetings with the Sultan. Thus their relations began to cool and found a final expression in a detailed critical paper published by Vámbéry in a London monthly in 1909 after the Sultan’s deposition by the Young Turks.

Afternoon program

The program of the afternoon session followed the morning program, but also added new viewpoints, dealing mainly with “Vámbéry the traveller and public figure”.

Barbara Kellner-Heinkele Turcologist and Islamist, the founder and ex-director of the Turcology Institute of Freie University, talked about Vámbéry’s famous Central Asian travels, comparing the effects of them with other travellers’ results. The title of the lecture was “Visions of Bukhara – A Comparative Look at the Travels of Arminius  Vámbéry and George Nathaniel Curzon”. This presentation discussed in a first step Vámbéry’s and Curzon’s level of information on Central Asia as displayed in their travel books and secondly compared their perception of the land and its peoples once they had made their own experiences. Third, the lecture attempted to show how the two men’s personal background and their mode of travelling determined their writing style. Finally, an overview was given of the development of European knowledge of Central Asia after Russia had forced open this region.

Vámbéry and George Nathaniel Curzon”. This presentation discussed in a first step Vámbéry’s and Curzon’s level of information on Central Asia as displayed in their travel books and secondly compared their perception of the land and its peoples once they had made their own experiences. Third, the lecture attempted to show how the two men’s personal background and their mode of travelling determined their writing style. Finally, an overview was given of the development of European knowledge of Central Asia after Russia had forced open this region.

After his Travels in Central Asia (1864), which gained him international fame, Arminius Vámbéry published over the next 40 years not only a number of additional books dealing with “the Orient” but also a multitude of eloquent, routinely written newspaper articles and essays on contemporary Central Asia. Although he never returned to the region, he was able to retain a certain prestige as a specialist of political, economic, social and cultural questions regarding an area that from a backwater of history had become the stage of the “Great Game”. Conquered by the Russians between 1863 and 1895, the so far unknown Central Asian territories quickly became a laboratory of Russian colonial efforts, showing successes as well as failures. Vámbéry was 31 years old when he made his trip from Tehran to Khiva, Bukhara, Samarkand and back (March 1863 – January 1864) under the most primitive conditions, practically without money or support, in regions where non-Muslims would usually meet with death when found out. Only 25 years later (1888), at the age of 29, George Nathaniel Curzon (1859–1925), Member of the English Parliament, made a comfortable trip from St. Petersburg via the Turkmen territory to Bukhara, Samarkand and Tashkent. Curzon lacked neither money nor official support and had no reason to fear for his life during his journey. “Russian Central Asia in 1889 and the Anglo-Russian Question” (1889) is the result of his travel, a hefty book based on the entire literature on Central Asia available to date in the major European languages and on the most recent Russian statistics. The book made him the foremost specialist of Central Asia in Great Britain and, with his later books on his travels in Persia, Afghanistan, East and South Asia, the leading authority on Asian affairs. The two men, so different in character, family background, education and worldview, were similar in their fascination for “the Orient”.

Professor Ruth Bartholomä, Turcologist and Islamist from the Albert-Ludwig University in Freiburg, was dealing with the effects of Vámbéry’s Central Asian travels, too, in her lecture “The perception of Arminius Vámbéry and his  journey in Central Asia – yesterday and today”; shedding light on the perception of Vámbéry and his journey in this region and other parts of the former Russian Empire or, respectively, the former Soviet Union, from the 19th century to the present.

journey in Central Asia – yesterday and today”; shedding light on the perception of Vámbéry and his journey in this region and other parts of the former Russian Empire or, respectively, the former Soviet Union, from the 19th century to the present.

When Arminius Vámbéry (1832–1913) travelled to Central Asia in the years 1863–1864, the region was not yet conquered by the Russian Empire and therefore constituted “forbidden territory” for the Europeans. But Vámbéry, disguised as a dervish, escaped detection and succeeded to return to Europe via Persia. After a warm-hearted reception in London and the publication of his travel account, he succeeded – without ever obtaining a university degree – in being appointed professor in Budapest. There were reactions not only in Europe, but also in Central Asia. In Central Asia, Vámbéry’s coup did not go unnoticed. According to later recollections, Vámbéry was not seen as a threat, but as a person eager for knowledge, deserving protection – and maybe even being worthy of respect for taking the risk of travelling in disguise. Today, the fact that there is still a memory of Vámbéry and his travel in Uzbekistan is clearly shown by a memorial tablet at the Ark Fortress of Bukhara, which

should be seen as one of many signs of the long-lasting tradition of friendship and mutual understanding. The lecturer stated that Vámbéry today functions as a figurehead for these values.

Historian Melek Çolak, Professor of Muğla University, researcher of the Turkish-Hungarian relations also dealt with Vámbéry’s famous travels and their possible political and diplomatic background, with the title “Thoughts on the  significance of Arminius Vámbéry’s travel in Central-Asia from the Ottoman, British and Russian angle”. The lecture presented and analysed Vámbéry’s journey and travel account in the context of the Central Asian politics of the day and mutual relationships of the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain and Russia.

significance of Arminius Vámbéry’s travel in Central-Asia from the Ottoman, British and Russian angle”. The lecture presented and analysed Vámbéry’s journey and travel account in the context of the Central Asian politics of the day and mutual relationships of the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain and Russia.

The famous Hungarian Turkologist Arminius Vámbéry, following a longer period of preparation in Istanbul, set out to his travel in Central-Asia disguised as a Muslim dervish. He managed to accomplish his journey with the knowledge and support of Ottoman political circles and to surmount the extreme difficulties with the help of other dervishes ubiquitous in the whole Islamic world. In a period when Great Britain and Russia were in sharp competition over Central Asia, both rivals were eager to know the experiences of Vámbéry heading for the region and wanted to benefit from the results of his journey. Vámbéry obtained a well-deserved international fame after publishing his travel account on his adventures in Central Asia.

The last lecture of the conference dealt with the controversial issue of Vámbéry’s international political activity: “Vámbéry as a public figure”. The presentation was held by two young researchers, Ferenc Csirkés Turcologist and Iranist, instructor of the Central European University and Gábor Fodor, Turcologist, young researcher of the Research Centre for the Humanities.

In Hungary Vámbéry is primarily known as a Turkologist and scholar, while in an international context he is also known for his political expertise in Central Asian and Ottoman matters and his diplomatic and clandestine activities. He had established contacts with British Foreign Office circles already around the time of his famous travel to Central Asia in 1863–1864, but these relations only became frequent between 1889 and 1913, when he regularly reported to the Foreign Office primarily about Ottoman affairs. The most prominent subject of his reports was his regular visits at the court of Sultan Abdulhamid II and his conversations with him. Acting as an intermediary between the British and the Ottomans with the tacit consent of the Sultan, Vámbéry intended to alleviate the conflict over the British occupation of Egypt and possibly forge an anti-Russian alliance. Naïve as he might have been in great power politics and secret diplomacy, Vámbéry’s reports provide a fascinating insight into the world power maneuvers of the last decades of the 19th through the first decade of the 20th century, a period that decided the fate of empires. The first part of the presentation gave a general outline of the context in which Vámbéry, a son of a poor Jewish family, could fashion himself as an exponent of Hungarian nationalism as well as British and Ottoman interests at the same time. The second part of the presentation focused on two files preserved at the Public Record Office in London and outlined the main topics of the correspondence.

After the closing of the conference, the Vámbéry commemorative exhibition was opened and a presentation of the Vámbéry memorial website was held at the Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The Oriental Collection of the Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (HAS), an extremely valuable section of which was established by Vámbéry, comprises a conspicuous material related to Vámbéry himself. Ágnes Kelecsényi, Head of the Collection and her colleagues have organized a small exhibition the official opening of which took place after the conclusion of the conference. In addition, Nándor Erik Kovács, curator of the Turkish Department of the Oriental Collection, with the assistance of a small working team, created a new website dedicated to Vámbéry’s life and activities. The website contains important pieces of information concerning the scholar’s life and work, as well as written and visual documents. Besides, brief surveys of different scholarly topics will also be available on the website which is planned to be continuously updated and enlarged in the future.

After the closing of the conference, the Vámbéry commemorative exhibition was opened and a presentation of the Vámbéry memorial website was held at the Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The Oriental Collection of the Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (HAS), an extremely valuable section of which was established by Vámbéry, comprises a conspicuous material related to Vámbéry himself. Ágnes Kelecsényi, Head of the Collection and her colleagues have organized a small exhibition the official opening of which took place after the conclusion of the conference. In addition, Nándor Erik Kovács, curator of the Turkish Department of the Oriental Collection, with the assistance of a small working team, created a new website dedicated to Vámbéry’s life and activities. The website contains important pieces of information concerning the scholar’s life and work, as well as written and visual documents. Besides, brief surveys of different scholarly topics will also be available on the website which is planned to be continuously updated and enlarged in the future.